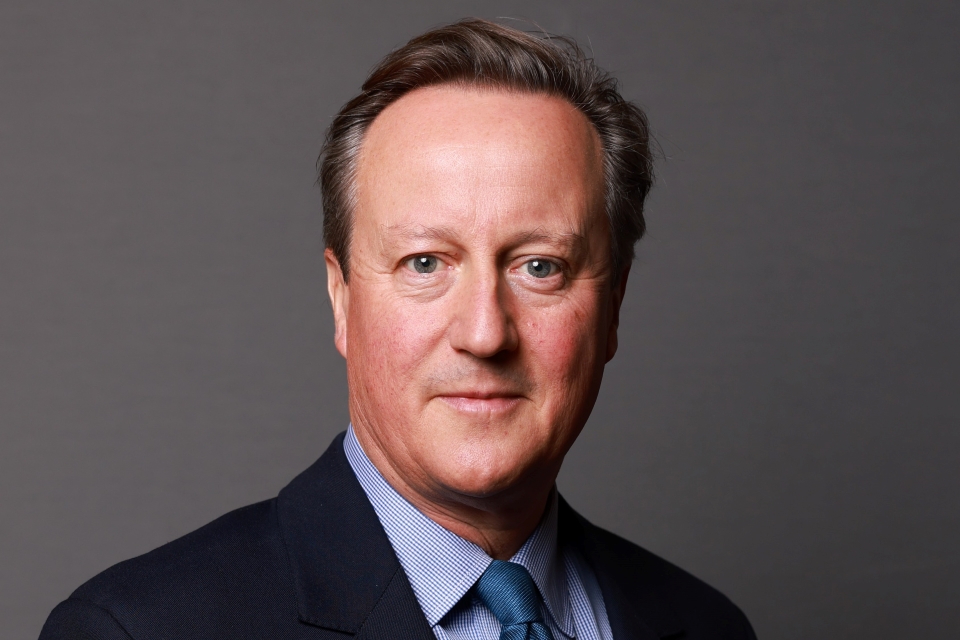

PM speech on life sciences and opening up the NHS

"We've got to change the way we innovate, the way that we collaborate, and the way that we open up the NHS."

Transcript of a speech given by Prime Minister at the FT Global Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Conference:

Thank you very much, Lionel, for that welcome and thank you to the FT for organising today’s conference. We’re not here, I’m afraid, to find a rescue remedy for the euro, but we are here because life sciences and the UK’s role in it is at a crossroads. Now, behind us lies a great history: Watson and Crick unravelling DNA, genetic fingerprinting, the first CT scan, the first beta blocker, the first test-tube baby, 34 Nobel Prizes in medicine, countless lives changed and countless lives saved. So we can be very proud of our past, but we cannot be complacent about our future.

The industry is changing, not just year by year but month by month. Now, there is pressure on healthcare budgets in the West and we’ve got our ageing populations. Meanwhile, we’ve got the emerging economies in the East and an explosion of knowledge. Now, I think that all these things together create a new paradigm for life sciences. And in this new paradigm, we must ensure that the UK stays ahead. Because yes, we’ve got a great leading science base. And yes, we’ve got four of the world’s top-ten universities. And yes, we have a National Health Service unlike any other.

But my argument today is this: these strengths alone are not enough, and that to keep pace with what’s happening we’ve got to change quite radically. We’ve got to change the way we innovate, the way that we collaborate, and the way that we open up the NHS.

Now, the two reports we’re publishing today are testament to our ambition: not just to sort of hang in there with a significant foothold in the global market, but to try to take an even bigger share of that market in the years to come. So here I want to set out my view of how the industry is changing and explain how we’re responding.

First, let me be clear about why this is so important to me and to this country. Life sciences is a jewel in the crown of our economy. It has consistently shown stronger growth than the UK as a whole, it accounts for 165,000 UK jobs and it totals over £50 billion in turnover. But the importance of life sciences isn’t just about its size; it’s about its nature.

Now, this government has set a clear goal to rebalance our economy: yes, that means less borrowing and less debt, but as important it means more investment, more exports, more designing things, making new products and selling them to the rest of the world. Innovation is the beating heart of this vision, and in this we are fortunate because Britain has something of a genius for it.

Just this year there have been some incredible breakthroughs. At University College London they discovered a protein that helps heart tissue repair itself. At Glasgow and Southampton they have developed a new way of culturing adult stem cells, paving new ground for the treatment of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. At Touch Bionics in Edinburgh they’ve unveiled the world’s most life-like prosthetic hand.

Invention is one of the things we do really well in the UK, and the appetite for that is soaring. Global pharmaceutical sales are predicted to grow up to 6% in the coming years. And in emerging economies, medical technology is achieving growth rates of over 12%. So if we’re going to build this more outward-looking, this more export-driven economy, then life sciences has got to play a big part in that.

But this isn’t just a calculation about what’s best for our economy. It’s also about what’s best for humanity. Earlier this year I was visiting a health clinic in Lagos in Nigeria. And I’ll never forget the sight of rows upon rows of mothers, sitting with their babies, waiting for their measles jabs and their tetanus jabs. The nurse told me that many of these babies would be dead without those injections, injections that cost less than £1 each.

Gandhi talked about the danger of science without humanity, but science with humanity can be just about the most powerful force for good on earth. And we’ve got to keep pushing for progress. Because yes, we’ve defeated some of the big killers of the past. But as old frontiers are conquered, new ones appear: lifestyle epidemics like obesity, diseases like dementia and diabetes. There are huge areas of unmet need and we’re relying on your industry to come up with some of the new answers.

This is why life sciences is so important: that virtuous circle of health, well-being and wealth. But just because progress has been remarkable, it doesn’t mean that it is inevitable. And as I see it, there are three big interlinking pressures on life sciences today.

First, as I’ve said, the pressure on healthcare budgets in the West. Governments and health systems are looking hard for savings, and often it’s the newest innovations that are the lowest-hanging fruit. Now second, there is the so-called pressure of the patent cliff. Last year, for instance, the heart-drug Lipitor made almost $11 billion in sales. Now, next year it comes off patent and soon there are bound to be several cheaper generic versions. Now, that might be good for those buying the drugs, but it doesn’t help you fund the next generation of drugs.

Third, and most importantly, there’s the pressure that new biological insights are having on your business model. The human genome took 13 years to decode and cost almost $3 billion. Today, a person’s genetic code can be decoded in a few weeks for just a few thousand dollars. As the CEO of Eli Lilly said, for decades discovery was like ‘feeling your way around a dark room and trying to make sense of what’s what. Suddenly the lights are on and we can see.’ Now, the explosion of information means that drugs and diagnostics can be much more tailored than ever before. It could be that in just 10 or 15 years, the idea of treating disease without reference to the patient’s genetic blueprint is quite simply unthinkable.

So together, if you like, these pressures have changed the game. The old ‘big pharma’ model is in flux. When it can cost $1 billion to develop a new drug, when it might only apply to a sliver of the population and when there’s a good chance it will fall at the last hurdle, then having thousands of highly paid researchers working on blockbuster drug after blockbuster drug just doesn’t make sense in the way that it used to. Now, we felt that with the fallout of the difficult decision made by Pfizer at Sandwich and AstraZeneca at Charnwood.

But I believe that in place of the old ‘big pharma’ model, a new model is emerging. It’s about more collaboration, more outsourcing, more early trials. We see it in the way that GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca and Manchester University have teamed up on inflammation research, pooling money and scientists in a move that could change millions of lives. We see it in the partnership between UCL and Yale University, working across the Atlantic to develop new cardio devices. We see it at Imanova, the Medical Research Council teaming up with London universities to break new ground in imaging, with a world-leading imaging centre at Hammersmith Hospital. You can call it translational medicine, you can call it experimental medicine; the fact is we see it, we recognise it, and we are determined to support it, to invest in innovation, to stoke early-stage investment, and to tear down the barriers to development.

Above all, it is becoming ever more essential to get your products tested and adopted in the NHS much more quickly. We’ve asked you what you needed, we’ve listened, and now we want to deliver. So let me give you some of the detail.

First, innovation. We’ve still got scientists who could be joining forces but aren’t, industry and clinicians who should be working together but don’t, and we are determined to change this. So we have made the decision, even in these difficult times, not only to protect the science budget, but we also announced an extra £495 million capital funding for science this year. We are creating a string of new Technology and Innovation Centres, with a high-value manufacturing centre already up and running and a cell-therapy centre to open next year. We’re investing £800 million in Biomedical Research Centres, which are home to groundbreaking collaborations, like the one between Pfizer and the Moorfields Eye Hospital to find a cure for macular degeneration. And we are putting huge efforts into strengthening Academic Health and Science Centres.

These are right in the vanguard of what’s happening in translational medicine, and they are a template for the world to follow. Just today the three London centres - Imperial, King’s Health Partners and UCL Partners - announced a new deal to share patient data, giving you huge potential for clinical research on specific diseases and underlining just how serious we are about catering to what patients and industry want. Now next we are pulling every lever possible to make the UK a much more attractive place in which to invest. From April 2013 there will be the new patent box offering a 10% tax rate on patent profits. GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca have already committed to new investment as a result and over the coming months we want to see more businesses follow suit. Add to this our corporation tax rates - on course to be the lowest in the G7 - and our generous tax credits for R&D. And I believe if you take those things together you have a compelling case for investing in research right here in the UK. And as you look to work more and more with smaller companies it is crucial that we do more to deal with the funding gap that so many people face - the so-called Valley of Death. So we’ve got a whole package of measures to bridge that gap - tax relief on angel investment up from 20% to 30%. The amount that can be invested in a single company in a year up from two million to 10 million and together these mean that if you build a business worth up to £25 million and then sell it, you’re going to be better off in the UK than you would be in the US.

Now obviously last week in the autumn statement we went even further. The Chancellor announced a new 50% tax break for the first £100,000 invested in a start-up. Plus as, if you like, a special offer for 2012, Olympics year, if you sell assets in that tax year and invest the proceeds in this seed scheme you will not pay a penny of capital gains tax on the assets that you’ve sold.

So for life sciences start-ups in particular, we’re doing all these things but we’re also doing something more. Today we announce £180 million catalyst fund targeted at new British ideas. This has got a simple and explicit aim: getting the best ideas through the proof of concept stage so we can get them into clinical development and get our entrepreneurs selling them around the world.

But for many of you here today the biggest hurdles are not tax or the other things I’ve spoken about, they are regulation and procurement. It can take 20 years from the discovery of a drug to getting it to market. Now that is hurting everyone: industry, taxpayers but above all patients, and the worst of it is that this is so unnecessary. The legislation is there in Europe to fast track lifesaving drugs, it is just woefully underused. Over 10 years it’s been used to fast track just 17 new drugs. That is why we’re consulting on a new early access scheme so that if patients are suffering in the advanced stage of a disease, and if there are no other treatments available, they are able to access innovative medicines much earlier in their development. As long as the drug qualifies for the scheme, it should be up to patients and doctors to decide whether they want to use it. Now this could mean brand new discoveries fresh from the lab being administered to patients here - here in the UK - before anywhere else in the world.

But the most crucial, the most fundamental thing we’re doing is opening up the NHS to new ideas because time and again we’ve heard the same thing from industry. We’ve got the treatments that work, we’ve proved they’re safe, they’ve been approved but we cannot get them into the NHS. In fact many in the industry say we can’t even get to the negotiating table. For instance, there is a finger-prick blood test that allows patients on anti-coagulation therapy to self-monitor their blood clotting time. It’s effective, it’s convenient and in the end it would be much cheaper for the NHS but still today less than 2% of the 1.25 million people in the UK on long-term anti-coagulation therapy are self-monitoring. Now this is happening with a whole host of drugs and treatments. It is a massive missed opportunity and in so many ways I believe it’s actually out of kilter with the whole spirit of the NHS because this is an organisation that has actually, over the years, thrived on innovation. When the link between lung cancer and smoking was first made, the portable defibrillator was first used, the CT scanner was first operated - the NHS can do innovation. This is the best of the NHS - resourceful and creative. Now we’ve got to take the best of the NHS to remedy the worst of it where it is bureaucratic and slow to take up new ideas.

Now that is what David Nicholson’s report, published today, is all about. If NICE have approved a drug we want to see that drug used consistently across the country. If new technologies are being used in one area we want to see others following suit. The end game is for the NHS to be working hand in glove with you as the fastest adopter of new ideas in the world, acting as a huge magnet to pull new innovations through right along the food chain from the labs to the boardrooms to the hospital bed.

Just look at our approach to tele-health - telemedicine - getting new technology into patients’ homes so they can be monitored remotely. We’ve done a trial, it’s been a huge success and now we’re on a drive to roll this out nationwide with an aim to improve three million lives over the next five years with this technology. Now this will make an extraordinary difference to people. Diabetics will be taking their blood sugar levels at home and having them checked remotely by a nurse; heart disease patients will have their blood pressure and pulse rates checked without leaving their home at all. This is dignity and convenience and independence for millions of people. And it’s not just a good healthcare story; it’s going to put us miles ahead of other countries commercially too as part of our plan to make our NHS a driver of innovation in UK life sciences.

Now there’s something else that we’re doing. It had a little bit of controversy over the weekend but it is the right thing to do, and that is opening up the vast amounts of data generated in our health service. From this month huge amounts of new data are going to be released online. This is the real world evidence that scientists have been crying out for and we’re determined to deliver it. We’ve seen how powerful the release of data can be. Thanks to the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust, the Institute of Psychiatry now has access to a database covering a quarter of a million patients. It’s got their brain scans, their medical records, their notes - a huge wealth of information all consented to, all anonymous - and that is helping them find new answers in the fight against dementia. It is simply a waste to have a health system like the NHS and not to do this kind of thing. So we don’t want to stop there.

We’re going to consult on actually changing the NHS constitution so that the default setting is for patients’ data to be used for research unless of course they want to opt out. Now let me be clear, this does not threaten privacy, it doesn’t mean anyone can look at your health records but it does mean using anonymous data to make new medical breakthroughs and that is something that we should want to see happen right here in our country. Now the end result will be that every willing patient is a research patient; that every time you use the NHS you’re playing a part in the fight against disease at home and around the world. Again, I would say this approach shows that we have listened and we are acting.

Now I know that you’ve heard promises like this before and that’s why I’ve asked Sir John Bell and Chris Brinsmead - two absolute experts in this field - to report back to me personally every six months on how we’re doing. Because believe me, we’re determined to convert these words and policy papers into action.

So let me finish today by reiterating my key message to you: we get that the game has changed and we are changing with it. We’re going to be more flexible, more competitive, more hungry for your business than ever before. And don’t doubt our ambition. Not just to stay in the game but to lead the game; not just to hold onto the big companies that we’ve got here in the UK but to see more businesses coming and setting up right here; not just to rest on past glories but to keep on striving for more breakthroughs. I want the great discoveries of the next decade happening right here in British laboratories; the new technologies born in British start-ups, proven in British hospitals. And in doing that I want to work with you. My door - the door to my team in Number 10 - is absolutely open and together I hope that we can work together for the good of the life sciences industry, for the good of the UK economy and ultimately for the good of the world. Thank you very much indeed for listening. Thank you. Thank you very much.

Right, we’ve got some time for questions. We’ve got the Chief Medical Officer here; we’ve got the Minister for Universities and Science here, we’ve got David Nicholson here flanked by the FT on either side; if there is a question that panel can’t answer I don’t know what we are going to do. Let’s start with the gentleman at the back over there. There is a roving microphone so it will come to you.