Speech at Imperial War Museum on First World War centenary plans

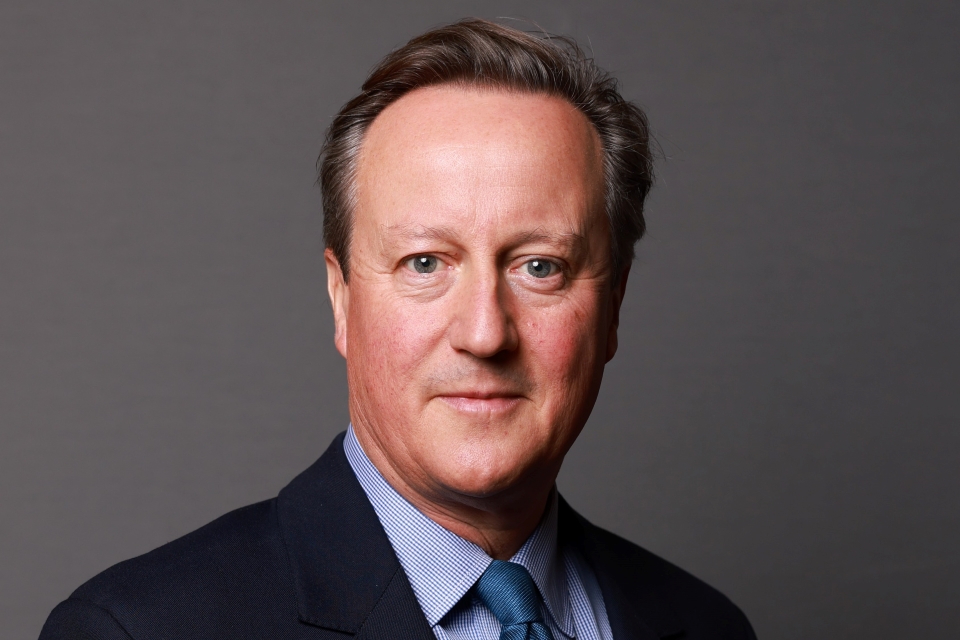

The Prime Minister gave this speech at the Imperial War Museum in central London on 11 October 2012.

Transcript of the speech given by Prime Minister David Cameron on Thursday 11 October about plans to mark the First World War centenary.

Prime Minister

Thank you very much, Andrew, for those words and thank you for all the work that you’ve done. This is, I think, a very exciting time for one of the finest museums in the world. It is a museum I particularly love. I will never forget when my mother brought me here as a boy and being absolutely captivated by everything within the museum. But almost more interesting was bringing my own children here, quite recently, they’ve come twice, I think, altogether. And realising that even when I was a boy there were still people alive who had fought in the Great War. There aren’t now, but my children were just as captivated and interested as I was. I think that speaks volumes about what we are discussing today.

The completion of transforming IWM London will see the Imperial War Museum reopened as the centrepiece of our commemorations for the centenary of the First World War. With that transformation, new generations will be inspired by the incredible stories of courage, toil and sacrifice that have brought so many of us here over the past century.

From the breathtaking sights of the hanging gallery to the unforgettable smell of the trenches, from great art - like this painting of The Menin Road by Paul Nash - to the many moving stories recorded from the front line, the Imperial War Museum is not just a great place to bring your children - as I said, as I’ve done - it is actually a special place for us all to come, to learn about a defining part of our history and to remember the sacrifice of all those who gave their lives for us, from the First World War to the present day.

We should also recognise that in the decade since the introduction of free access to our national museums, the annual number of visitors here has increased by almost two-thirds. I passionately believe we should hold on to this heritage and pass it down the generations. That is why, even in difficult economic times, we are right to maintain free entry to national museums like this. It is why we will continue to do so.

Today, I want to talk about our preparations to commemorate the centenary of the First World War. I want to explain why, as Prime Minister, I am making these centenary commemorations a personal priority, and I want to set out some of the steps we are taking to make sure we really do this properly as a country.

Let me start with why this matters so much. Of course, as Andrew said, there will be some who wonder: why should we make such a priority of commemorations when money is tight and there is no one left from the generation that fought in the Great War?

For me there are three reasons. The first is the sheer scale of the sacrifice. When they set out, none of the armies had any idea of the length and scale of the trauma that was going to unfold. For many, going off to war was a rite of passage. Many of them were excited; they would eat better than they had when they were down the mines or in the textile mills. They would have access to better medical care, and many thought they’d be home by Christmas, anyway. There is the story of the Russian High Command asking for new typewriters and being told the war wouldn’t last long enough to justify the expenditure.

As Major J V Bates from the Royal Army Medical Corp wrote:

Being our first experience of war, we men were not so much frightened, as very excited. It wasn’t until after two or three weeks of continually fighting rear-guard action, reconnaissance patrols and seeing our mates killed and wounded that the real horror of it came home to us. And if everyone else was as frightened as I was, then we were all petrified.

Four months later, one million had died in the heavy artillery battles that actually came before the digging of the trenches. Four years later, the death toll of military and civilians stood at over 16 million, nearly 1 million of them Britons. 20,000 were killed on one day of the Battle of the Somme. To us, today, it seems so inexplicable that countries which had many things binding them together could indulge in such a never-ending slaughter, but they did. The death and the suffering was on a scale that outstrips any other conflict. We only have to look at the Great War memorials in our villages, our churches, our schools and universities.

Out of more than 14,000 parishes in the whole of England and Wales, there are only around 50 so called ‘thankful parishes’, who saw all their soldiers return. Every single community in Scotland and Northern Ireland lost someone, and the death toll for our friends in the Commonwealth was similarly catastrophic. In the 1920s over 2,400 cemeteries were constructed in France and Belgium alone, while today there are cemeteries as far afield as Brazil and Syria, Egypt and Ireland.

Rudyard Kipling, whose own son was lost, presumed killed, at the Battle of Loos in 1915, described the construction of these cemeteries as the biggest single bit of work since any of the pharaohs, and as he pointed out, the pharaohs only worked in their own country. Such was the scale of sacrifice across the world. The then Indian empire lost more than 70,000 people; Canada lost more than 60,000, so did Australia; New Zealand, 18,000. And as part of the UK at the time, more than 200,000 Irishmen served in the British forces during the war, with more than 27,000 losing their lives. This was the extraordinary sacrifice of a generation. It was a sacrifice they made for us, and it is right that we should remember them.

Second, I think it is also right to acknowledge the impact that the war had on the development of Britain and, indeed, the world as it is today. For all the profound trauma, the resilience and the courage that was shown, the values we hold dear: friendship, loyalty, what the Australians would call ‘mateship’. And the lessons we learned, they changed our nation and they helped to make us who we are today.

It is a period of our history through which we can start to trace the origins of a number of very significant advances: the extraordinary bravery of Edith Cavell, whose actions gained such widespread admiration and played an important part in advancing the emancipation of women; the loss of the troopship SS Mendi, in February 1917 and the death of the first black British army officer, Walter Tull, in March 1918, are not just commemorated as tragic moments, but also seen as marking the beginnings of ethnic minorities getting the recognition, respect and equality they deserve.

The improvements in medicine were dramatic. In 1915 wounds which became infected resulted in a 28% mortality rate; by 1917 the use of antiseptics saw the death toll drop to just 8%. Plastic surgery developed into a well-established speciality over the course of the war.

At the same time there were hugely significant developments in this period, which, frankly, darkened our world for much of the following century. The advance in technology transformed the nature of war beyond recognition. The tanks and aircraft of 1918 were the forerunners of those that fought with such devastation in World War II. They would have been almost unimaginable for the cavalry regiments that set out in the autumn of 1914.

The war’s geopolitical consequences defined much of the twentieth century. It unleashed the forces of Bolshevism and Nazism and, of course, with the failure to get the peace right, the great tragedy was that the legacy of ‘the War to end all wars’ was an equally cataclysmic Second World War, just two decades later.

So I think for us today to fail to recognise the huge national and international significance of all these developments during the First World War would be, frankly, a monumental mistake.

There is a third reason why this matters so much. It is more difficult to define, but I think it is perhaps the most important of all. There is something about the First World War that makes it a fundamental part of our national consciousness. Put simply, this matters not just in our heads, but in our hearts; it has a very strong emotional connection. I feel it very deeply. Of course, there is no one in my family still alive from the time, or anything close to it. My grandfather, my uncle, my great uncle all fought in the Second World War. I have always been fascinated by what happened to them and tried to listen to their experiences.

Even though the family stories that I’ve heard direct from the participants, as it were, were all from World War II, there is something so completely captivating about the stories that we read from World War I. We look at those fast fading sepia photographs of people posing stiffly and proudly in their uniform. In many cases it was the first and last image ever taken of them, and this matters to us.

The stories and the writings of the Great War affect us too. That mixture of horror and courage, suffering and hope; it has permeated our culture. From the poems of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, my favourite book, Robert Graves’s memoirs recounting his time in the Great War, Good-Bye to All That. To modern day writers like Sebastian Faulks, from Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, focusing on the aftermath of trauma, to War Horse, showing the sacrifice of animals in war. Current generations are still absolutely transfixed by what happened in the Great War and what it meant.

The fact is, individually and as a country, we keep coming back to it, and I think that will go on. This is not just a matter of the heart for us in Britain. It is a matter for the heart for the whole of Europe and beyond. From The Last Post Association, whose volunteers have played every night at the Menin Gate since 1928, to Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery, to the Memorial to the Missing, in Belgium, which is the largest British war cemetery in the world, visited by nearly half a million people every year, still today, to the battlefield memorials right across Western Europe.

For me, when asked: what is the most powerful First World War memory you have? It is going to visit the battlefields at Gallipoli. I’ll never forget going, having a fantastic Turkish guide who showed me the beaches we were meant to land at, the beaches we did land at, the fight that went on up those extraordinary hills. One of the most powerful things I’ve ever seen is the monument erected by the Turks in Gallipoli. Before I read you the inscription, think in your mind, think of the bloodshed, think of the tens of thousands of Turks who were killed, and then listen to the inscription that they wrote to our boys and to those from the Commonwealth countries that fell. It is absolutely beautiful, I think. It goes like this:

‘Those heroes who shed their blood and lost their lives, you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore, rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us, where they lie, side by side, in this country of ours. You, the mothers, who sent their sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land, they shall become our sons as well.’

So beautiful, beautiful words on this First World War monument. For me, those words capture so much of what this is all about. That from such war and hatred can come unity and peace, a confidence and a determination never to go back. However frustrating and however difficult the debates in Europe, 100 years on we sort out our differences through dialogue and meetings around conference tables, not through the battles on the fields of Flanders or the frozen lakes of western Russia.

Let me turn to the plans for the centenary. Last November I appointed former Naval doctor Andrew Murrison as my special representative. I am very grateful to him for the excellent work he has been doing in assembling ideas from across Government and beyond, and for putting the UK among the leaders in this shared endeavour and for laying the foundations of our commemorations. Today, I am honoured to be able to say that he is going to be joined by some of the most senior figures in British public life, including Tom King, George Robertson, Menzies Campbell, Jock Stirrup and Richard Dannatt. That’s two former Secretaries of State for Defence, one of whom was also a Secretary General of NATO, a former Chief of the Defence Staff, a former Chief of the General Staff. They’ll be joined by others, including world leading historians, like Hew Strachan, and world class authors like Sebastian Faulks. I hope they’ll provide senior leadership on a new advisory board that is going to be chaired by the Secretary of State for Culture, Maria Miller.

Our ambition is a truly national commemoration, worth of this historic centenary. I want a commemoration that captures our national spirit, in every corner of the country, from our schools to our workplaces, to our town halls and local communities. A commemoration that, like the Diamond Jubilee celebrated this year, says something about who we are as a people.

Remembrance must be the hallmark of our commemorations, and I am determined that Government will play a leading role, with national events and new support for educational initiatives. These will include national commemorations for the first day of conflict, on 4th August 2014, and for the first day of the Somme, on 1st July 2016. Together with partners like the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and the custodians of our remembrance, the Royal British Legion, there will be further events to commemorate Jutland, Gallipoli and Passchendaele, all leading towards the 100th anniversary of Armistice Day in 2018.

The centenary will also provide the foundations upon which to build an enduring cultural and educational legacy, to put young people front and centre in our commemoration and to ensure that the sacrifice and service of a hundred years ago is still remembered in a hundred years’ time.

Now, the Imperial War Museum is already leading the First World War Centenary Partnership, a growing network of over 500 organisations, helping millions of people across the world to discover more about life in the First World War and its relevance today. Today we are complementing that with a new centenary education programme, with more than £5 million of new Government funding. This will include the opportunity for pupils and teachers from every state secondary school to research the people who served in the Great War, and for groups of them then, crucially, to follow their journey to the First World War battlefields. I think that will be a great initiative and really welcomed by secondary schools and secondary school pupils.

We are also providing a further £5 million of new money, in addition to the £5 million we have already given to support transforming IWM London - this project right here at this incredible museum. It will match contributions from private, corporate and social donors.

So our commemorations, if you like, will consist of three vital elements: a massive transformation of this museum to make is even better than it is today, a major programme of national commemorative events properly funded, given the proper status that they deserve, and third, an educational programme to create an enduring legacy for generations to come. All of this will be overseen by a world class advisory board chaired by the Secretary of State for Culture, supported by my own special representative Andrew Murrison.

And that is not all, because we stand ready to incorporate more ideas because a truly national commemoration cannot just be about national initiatives and government action, it needs to be local too. So the Heritage Lottery Fund is today announcing an additional £6 million to enable young people working in their communities to conserve, explore and share local heritage of the First World War.

That is in addition to the £9 million they have already given to projects marking the centenary, including community heritage projects. And they are calling for more applications; they are open to new ideas, to more thinking. So whether it is a series of friendly football matches to mark the famous 1914 Christmas Day truce, or the campaign led by the Greenhithe branch of the Royal British Legion to sow the Western Front’s iconic poppies here in the UK, I think we should get out there and make this centenary a truly national moment, but also something that actually means something in every locality in our country.

So, in total over £50 million is being committed to these centenary commemorations; I think it is absolutely right they should be given such priority, as I have explained. As a twenty-year-old soldier wrote just a week before he died: ‘But for this war, I and all the others would have passed into oblivion like the countless myriads before us, but we shall live forever in the results of our efforts.’

Our duty towards these commemorations is clear: to honour those who served, to remember those who died, and to ensure that the lessons learnt live with us forever. And I think that is exactly what we can do with these commemorations.

I think we have got a moment or two for questions or points or any observations anyone would like to make.

I mean what I said about wanting ideas; I think we have a good framework here of national commemorations, the Heritage Lottery Fund I think can fund a lot of local activity but I am sure out there there are still some great history or commemorative projects that can be brought to book. So I hope people can come up with them.

Question

Prime Minister, one key element I think of the commemorations is reconciliation, and on the island of Ireland of course you referred to the huge sacrifice of Irishmen North and South who died in the Great War. Following on from Her Majesty the Queen’s visit to Dublin, I think there is a great opportunity here not to exploit the commemoration but the commemoration can be a means of recognising the contribution that those thousands of Irishmen from the Irish Republic made in defending our freedom and drawing them ever closer in harmony with the United Kingdom.

Prime Minister

I think you are absolutely right. It is always one of the figures that I think people find most staggering when you look at how many people from the island of Ireland, then part of the United Kingdom - even though there was the great argument raging before the First World War that was then put on hold - how many people volunteered to fight in the First World War.

And I am hoping with the Taoiseach to go and visit some of the sites in Belgium where a lot of Irishmen gave their lives. Because I think there is a relevance today of what happened then about working on the Reconciliation Agenda which is, I think, going extremely well; the Queen’s visit and all the other things that have happened recently are part of that. So I think that is a very, very good point.

Question

Are you able to say anything about the plans for the marking of the start of the centenary programme on the weekend of the - Monday, August 4th 2014? And just to say that you would be more than welcome to join us at our centenary march in Folkestone down the Road of Remembrance down to the harbour.

Prime Minister

That is a very good point because we have got these big national events, obviously the day of the outbreak of the First World War, the first day of the Somme, Gallipoli, Jutland, and I think we are working very closely with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission - I think Andrew might want to say something and tell us about what the thinking is on 4th August.

Andrew Murrison

Yes, we have a marvellous Commonwealth War Grave Commission site that I don’t think enough people know about. It is Brookwood; it is the largest one we have in the United Kingdom, Prime Minister, and working with our Commonwealth War Grave partners the idea will be that we shall commemorate the first day of Britain’s involvement in the Great War at Brookwood.

But also working with Damian Collins who chairs the Step Short project in Folkestone, which is a wonderful, wonderful example of the sort of thing you were discussing in terms of projects for the future. I think that is a wonderful way of commemorating the logistics down there and, of course, it is the major port of embarkation for most of the young men leaving for the continent.

So that is an example of one of the projects I think we need to see more of in the two years available to us, and I look forward to seeing the Step Short project as a very important part of the 4th August 2014.

Lord Faulkner (All-Party War Heritage Group)

I am Richard Faulkner, I chair the parliamentary All-Party War Heritage Group and you will remember, Prime Minister, that I wrote to you in July last year after we had had a meeting addressed by representatives of other countries, particularly Australia and Belgium on what their plans were. We were expressing concern then that we seemed to be a little bit behind what other countries were doing.

I just want to comment to say that I think your appointment of Andrew Murrison later in the course of 2011 and the announcement you made today, I think, puts us right back at the heart of what is happening. We shall be very grateful to you for that and we would like to help in any way we can to make sure it is a great success.

Prime Minister

Well, thank you very much, Richard; I am very pleased you say that. I think Andrew has done a great job. We are working very closely, obviously, with Australians and New Zealanders and others - Canadians - to make sure that we are all doing similar types of things and also joining in for so many of the commemorations.

I have obviously thought about this carefully and I have tried to sum it up at the end there, it seems to me the three keys to this are, first of all, what is happening here at the Imperial War Museum. There is no point in building a whole new museum, we have got this fantastic museum here and I think the best legacy we can possibly have is actually to improve it in the way that is being suggested, and the new money being announced today, I think, will make an enormous difference to what is already a fantastic museum.

I think then the individual events commemorating those things that happened between 1914 and 1918, and I identified some of them, I think that is the second part of it. The third, and the bit that I think can still expand further, is all of the local initiatives that the Heritage Lottery Fund and others can help fund, because I am sure people will come up with extraordinary interesting and exciting ideas.

If you look at all the interest there is in people tracing family trees, understanding family history; I am involved in a constituency case in my own constituency at the moment about someone has got a particular person who died in Chipping Norton at the end of the War and there is an argument raging about whether he should be included on the War Memorial or not.

And so to say that people aren’t interested - they are, there is a fascination with these things that I think we can tap into and I think we have got the framework now for making sure we get this right and I am very, very grateful for what you say.

Thank you again for coming, thank you Imperial War Museum for hosting us, and let’s get on and do it right. Thank you very much.